Omaswa from Uganda: `Donors want a controlling say’

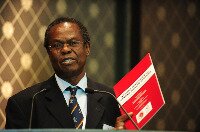

Dr. Francis Omaswa |

Part five of the 8-part series In the Driver’s Seat: A Series on Country Ownership of Health Programs. Dr. Francis Omaswa is the founder and executive director of the African Centre for Global Health and Social Transformation, based in Kampala, Uganda. Omaswa, a medical doctor, was the Director General for Health Services in the Ministry of Health in Uganda for seven years, and currently is a senior advisor to the Ministerial Leadership Initiative for Global Health.

Q: What is your assessment of the state of country ownership in health programs?

A: Donors with the money want to have a controlling say in the planning of the programs. That’s basically it. The results are not as expected. From our side, we also have been complaining. I have been talking for a long time -- until there is sufficient ownership in the developing countries that are driving the programs, the programs will not be sustainable.

Q: How do you define country ownership?

A: It means the affected communities recognize they have issues that need to be addressed and the responsibility is primarily theirs and no one else’s. That is crucial to everything else that happens later. Until beneficiaries recognize the problem, then solutions that come are not going to work.

Q: Can you give me an example of how the current system isn’t working?

A: Take the human resources for health crisis. Until just a few years ago, the cost for human resources of the country was the responsibility of the country alone and not of the donors. Donors said it is not something for us, because it is not sustainable. So after implementing policy, which excluded support for human resources for health, after some time everyone realized things were not working because the lack of human resources was creating a bottleneck. This lack of support for human resources meant we stopped recruitment of staff across the public service. There were vacancies, there were no health workers in certain jobs, and still donors refused to support investment in health workers. That’s one example.

Another example: Donors work often through NGOs, and that makes the government powerless. Donors give money to NGOS and do not link those programs with government supervision, do not link the NGO program with government programs, so the result has been that the NGOs do their thing, and the government has no control over it. We end up with uncoordinated interventions.

Q: Do you have an example from Uganda?

A: Yes, antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) when they were introduced. The NGOs had money to buy branded drugs. The government was distributing generic ARVs. The patients getting the branded drugs were bragging, telling patients with generic drugs that the generic drugs were useless. That was a major cause of problems here. Also, clinics that were run by donor funds were quite often located in the same area as the government programs, sometimes even in the same building. The donor clinics had nice furniture and looked great, while the government clinic was dirty with old furniture. Workers were paid more in the donor clinics. The public sees clearly something wrong with one side of the clinic. One place is working, the other one is not.

Q: What should donors be doing now?

A: These things are well documented, written down in the Paris Declaration and readjusted in Accra. I suggest two directions. The first one is to support the governments, work to provide stronger leadership capacity of the government. This was considered not to be a donor business. Support to Ministry of Health was not popular. It was considered not to be the responsibility of the donors. This is important – the quality of the leadership of the ministers, the technical ability of the staff, all that should be part of the donors’ help to a country. The second intervention is to support the growth inside countries of institutions that could support the government -- health partner resource institutions cultivated and grown inside the country, which not only can support the government but also hold the governments to account when they don’t perform. That’s where the future lies.

In the Driver’s Seat: A Series on Country Ownership of Health Programs

Part 1: WHO's Chan: 'Some countries are angry'

Part 2: Shah: 'We want real outcomes in health'

Part 3: Ethiopia’s Tedros: No ownership, no scale

Part 4: Wisman: Donors need to `take a little risk’

Part 6: From Nepal: `We build step by step’

Part 7: From Mali: `We have a lot of control now’

Keyword Search

MLI works with ministries of health to advance country ownership and leadership. This blog covers issues affecting the ministries and the people they serve.

Connect with Us

![]()

![]()

Categories

Blogs We Like

- Africa Can End Poverty

- Africa Governance Initiative

- Behind the Numbers

- CapacityPlus

- Center for Global Health R&D Policy Assessment

- Center for Global Development: Global Health Policy

- Center for Health Market Innovations

- Global Health

- Global Health Hub

- Global Health Impact

- The New Security Beat

- PAI Blog

- RH Reality Check

- Save the Children

- Transparency and Accountability Program

Contact Us

Please direct all inquiries to

Comments